In the worst housing crisis of the last 50 years, home ownership in Iceland has decreased by more than 10% in a decade. Just before the 2008 crash over 86% of homes nationwide were owned by their residents. Since 2012 the rate has been floating around 78%. More people are renting even though buying a home is considered a priority. Besides, rent can be more expensive than monthly mortgage repayments. For those who can afford the down payment, buying is an obvious choice.

However, in the current scenario saving up for a down payment is not that simple. Property prices escalate faster than purchasing power and banks aren’t lending as easily. 90% mortgage loans haven’t been around for a while, and the vacation rental industry is swallowing every reasonably located studio and one-bedroom flat. Few affordable apartments are being built and buyers have to fight over whatever is available.

As a consequence, micro-flat blocks have been popping up as an affordable alternative. Tiny homes are culturally acceptable in dense cities like Hong Kong and Paris. But Icelanders spend more time at home than the residents of busier capitals, and typically form a family early and need to move on to a bigger home. It’s hard to see a claustrophobia-inducing shoebox apartment as a sensible long-term investment.

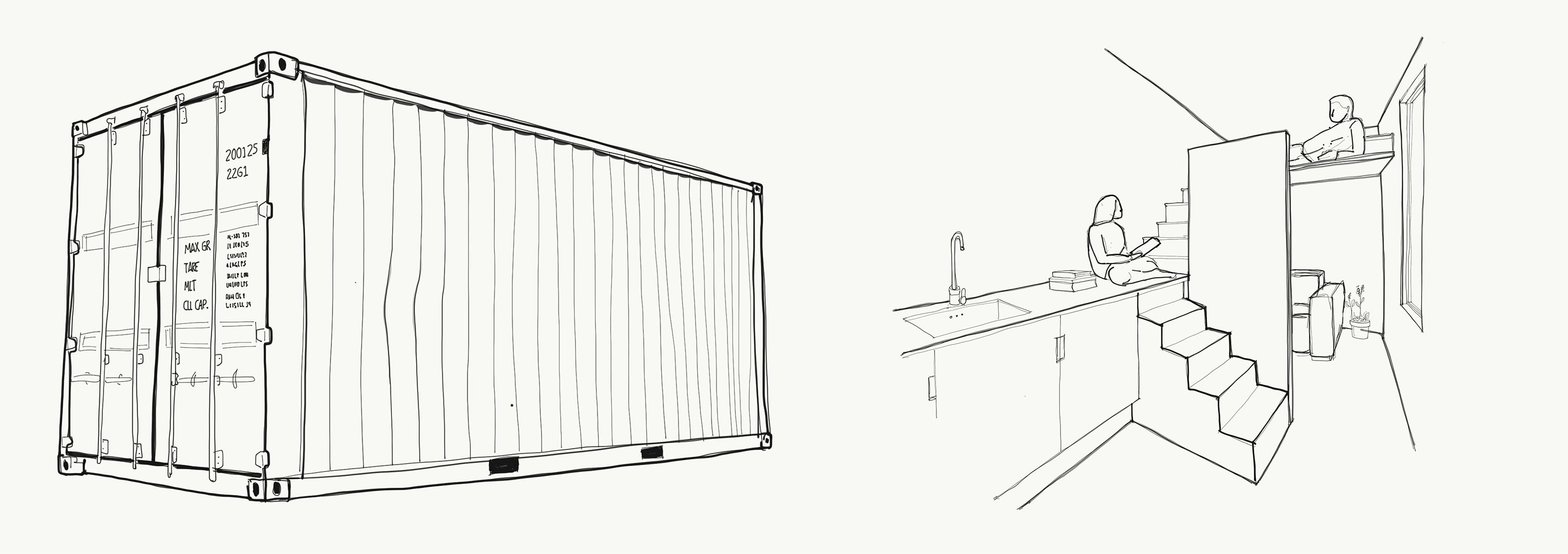

When a 8.8 magnitude earthquake hit Chile in 2010 leaving more than 20 thousand families homeless, Alejandro Aravena’s architecture studio Elemental employed a clever solution to rehab some of the areas affected.

“We had to build a hundred houses with a subsidy of $7,500 per family, which in the best of the cases allowed for 36m2 of built space. So we thought of a typology that allowed for houses to expand.(…) After a year and an average investment of $750, each property value was beyond $20,000. Still, all the families have preferred to stay and keep on improving their homes, instead of selling them.” – Alejandro Aravena.

The homes Elemental built include a kitchen/lounge, a bathroom and two bedrooms. They can be expanded, at minimal expense, into exactly double the original size. In a Northern European, first-world, middle-class scenario the circumstances are not as brutal, but the housing crisis creates an opportunity for innovation. And some of the most innovative ideas emerge in situations of calamity and despair.

While the Chilean design works perfectly in the context it was meant for – very low income communities, sometimes former slums, in a tropical climate – with some adjustments the concept can fit the socio-economic reality, building regulations and climate of Iceland.

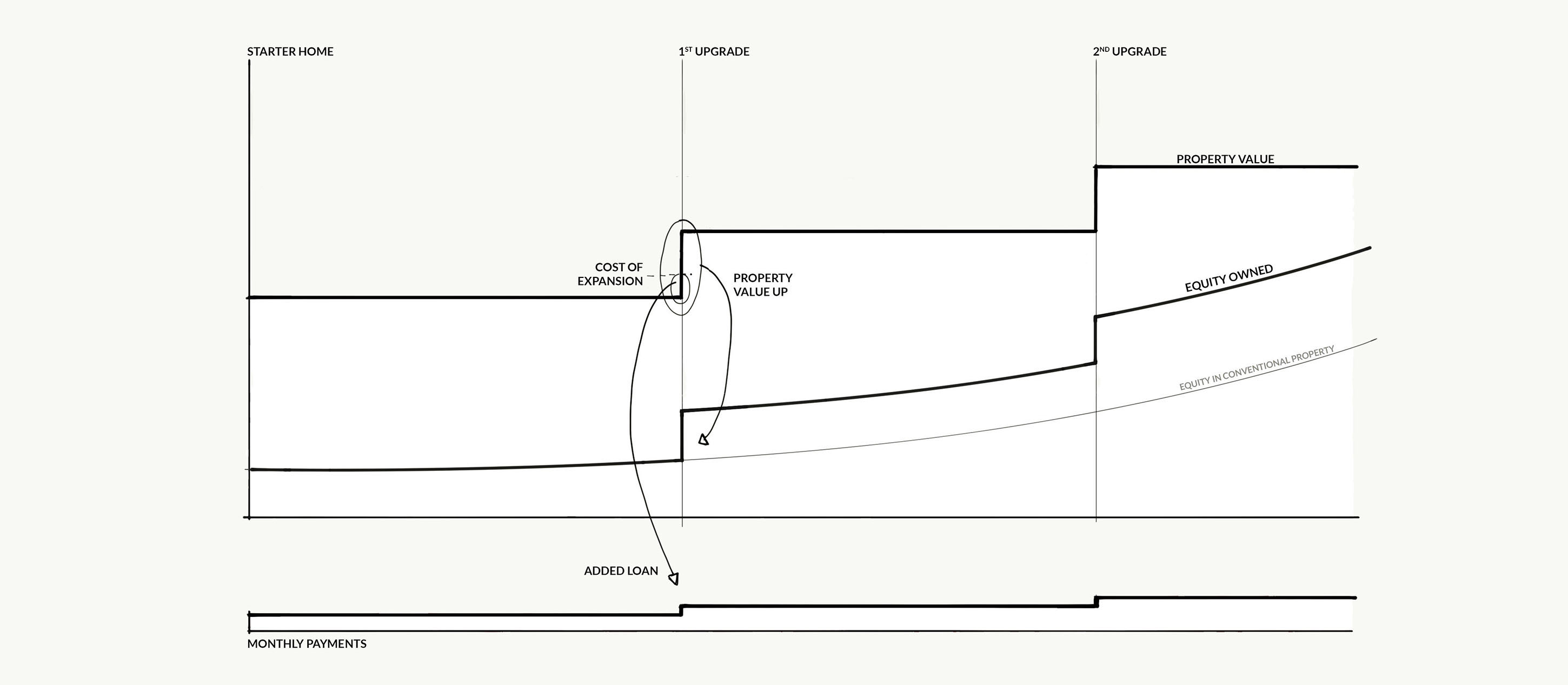

Property development and construction have almost always been very profitable. The more they build, the more they profit. Hence the inclination towards more luxurious properties with bells and whistles, where every detail and accessory is marked up. When it comes to a minimal, functional housing unit that can have its area doubled, some of the profits change hands. It’s still viable for the developer to build it. But as the new proprietors put in a little effort, they will reap a large chunk of the gains generated, in the form of increased equity. Because, as in the Chilean example, each square metre added to the house will cost less than what it’s worth in the market.

“Half a good house is better than a small house: it gains value over time.”

“Half a good house is better than a small house: it gains value over time.”

Besides, people place higher value on products they partially co-create. That’s a cognitive bias known as the IKEA effect. While in some cultures it could be a challenge – or even a legal hurdle – to let people finish parts of their home, that’s something Icelanders have always done. Maybe by force of habit, maybe due to the non-existence of cheap labour in the country, renovations are often bricolaged with the help of a couple of friends, and paid in pizza.

Incremental housing could be a triple win in developed countries. It’s an opportunity for the municipality to tackle the housing crisis without dispensing hefty subsidies; it’s profitable for the developers (although perhaps not the most profitable product); and an excellent deal for the buyers – who can get on the property ladder earlier with reduced financial burden, customize and expand their home according to needs and means, and accumulate equity faster than in a regular property. By paying off the mortgage a few years earlier or simply selling the property after a lock-in period, the buyers can realize gains regardless of an overall housing market appreciation.

–

In 2017, in an initiative to assess the sheer demand for affordable housing, the city of Reykjavík launched a call for ideas (Hagkvæmt húsnæði hugmyndaleit) and announced seven lots in the municipality to be sold exclusively to groups that presented winning proposals. The architect-led property development group Vaxtarhús won the right to develop the most central one of the lots and will introduce the first incremental housing project ever implemented in such an economically advanced country.

–

Rafael Campos de Pinho is an architect at RCDP arkitektar and partner at Vaxtarhús.