How does one make a building plans for Reykjavík’s most fragile natural area without destroying heritage dating back to the last ice age? HA interviews landscape architects Yngvi Þór Loftsson and Þráinn Hauksson.

Summary by Arnar Fells.

Photos by Ólafur Már Sigurðsson.

Öskjuhlíð is one of Reykjavík’s biggest recreational areas. It’s a prolific hill standing some 60 meters above the sea level topped by Perlan, a building that looks like half a disco ball resting on top of water tanks serving the capital.

Not long ago, the area was largely ignored as an outdoor recreation area. Today, it is one of the biggest outdoor recreation areas in Reykjavik. Travellers flock to Perlan to enjoy the view over the city, students attending Reykjavík University enjoy the proximity of the nature, sun-deprived citizens of Reykjavík rush to the beach at Nautólfsvík every time the temperature goes above 10 degrees, and pagans from all around the world await the pagan temple now rising in the south end of Öskjuhlíð.

But how does one make a building plans for Reykjavík’s most fragile natural area without destroying heritage dating back to the last ice age?

Perlan on top of Öskjuhlíð and the tower of Reykjavík´s cathedral Hallgrímskirkja.

Planning the wild

The land-use plan and developments of the Öskjuhlíð area where made by landscape architect Yngvi Þór Loftsson of Landmótun, back in 1998. Loftsson has previously worked in developing the highlands of Iceland as well as other remote recreational areas. His approach to Öskjuhlíð builds upon terrain analysis, based on the natural characteristics of the area. The approach has been applied to the planning of different areas varying greatly in size, which means that the degree of precision in the approach can also vary greatly. The accuracy of the analysis depends on the size and nature of the site, and how much relevant information is available. According to Loftsson, “The most important factor is how well the natural conditions are understood.“

Fingerprints of the past

Öskjuhlíð contains many traces of geological history from the latter part of the Ice Age. Around 11 000 years ago, the sea level was much higher than it is now, meaning that Öskjuhlíð was an island at that time. Traces from that era include glacial ridges and boulders smoothed by the sea, which lie encircling the area at 43 meters above sea level. Next to Fossvogur are the Fossvogur banks, sediments from the Ice Age, in which mineralized shells can be found. These shells provide evidence that suggests that the sea temperature at the time was similar to what it is now.

A wide variety of historical artifacts can also be found in Öskjuhlíð. The oldest artifacts are related to farming, for example Víkursel which was a type of livestock-dwelling for Vík, the main farmstead in Reykjavík. The farmers of Reykjavík had both forestry and livestock-dwelling utilities in that area, and the remains of sheepfolds & shelters are still visible. Other relics include landmark stones, thoroughfares and peat ditches. Most of the war relics land-found in the capital are preserved in Öskjuhlíð. These include concrete bunkers, trenches made of turf and stones, air defense bunkers, and defense walls.

Öskjuhlíð was in a state of disarray in the aftermath of the Second World War due to construction work carried out by the occupying troops. It was following that time that revegetation efforts began, and today there is continuous forest spreading across the southwestern slope. There are around 135 documented species of vascular plants in Öskjuhlíð, about one third of all species of flora in Iceland. Birdlife is also diverse, with around 84 species sighted in the area, 10 of which nest there annually.

“The objective of the land-use plan was, among other things, to protect the natural and historical relics, and to make Öskjuhlíð more accessible for recreational activities by adding paths and connecting them to adjacent outdoor recreation areas and neighborhoods. Increasing the diversity of outdoor activities available year-round, revive beaches, and improve the sailing facilities at Nauthólsvík.“ says Yngvi.

Recreation resilience

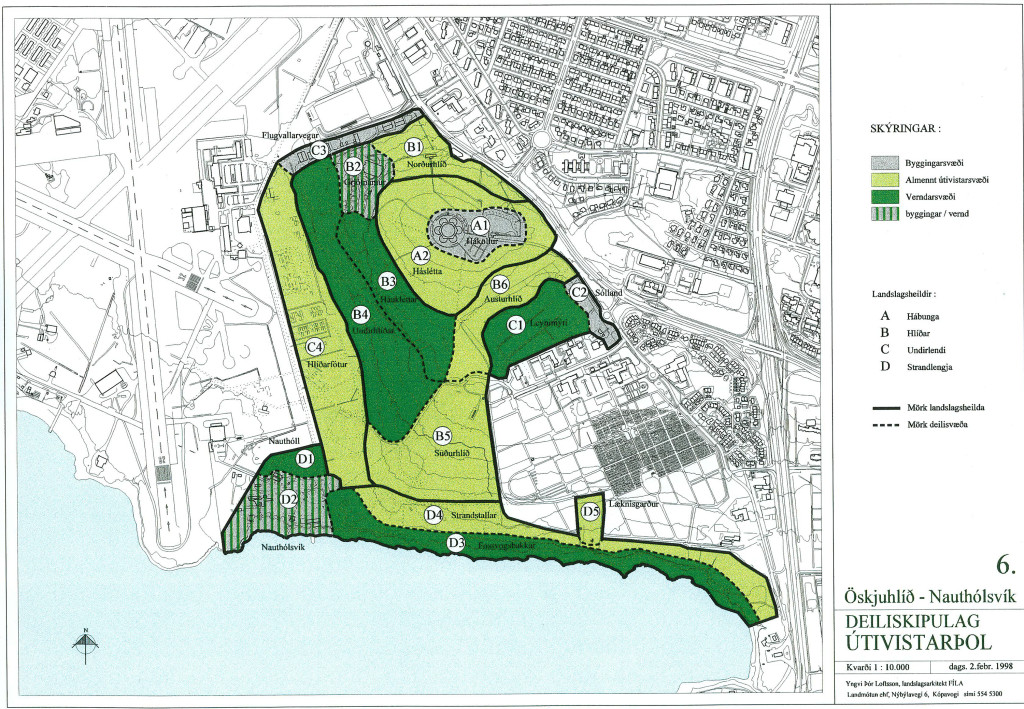

The land was grouped into four landscape units, uniform geographical areas are defined by their natural features, landscape and land use: Hábunga, Hlíðar, Undirlendi, Strandlengja. This laid the foundations for the creation of specific organizational units, which simplify the demarcation of areas and decisions about land use. In accordance with this concept, the divisions were classified by natural conditions and man-made factors in terms of their “recreation resilience”, the level of recreational activity the area can tolerate without incurring significant damage.

Image from Landmótun showing the four landscape units. Grey: building sites. Light green: public recreation areas. Green: protected areas. Stripes: Constructions and protection areas.

Specific protected areas

These areas are highly sensitive to disturbances and this needs to be taken into account when developing the area. Paths need to be made of gravel and laid with utmost care. Within these sanctuaries are the Fossvogur banks, which are protected under nature conservation laws due to their Ice Age sediments; as well as Háuklettar and Undirhlíðar, where the highest tidemarks from the end of the Ice Age are visible; and Leynimýrar, which increases the diversity of vegetation and birds.

Public outdoor recreational areas

Areas that are not as fragile and can therefore be used for all public recreation activities without destroying the land. In these areas one can find playgrounds, sports fields, tree cultivation areas and paved paths. They are intended to distinguish between protected regions and construction zones, and to connect adjacent outdoor and residential areas. The general outdoor areas are Hábunga, the north and south slopes, at the foot of the hill, and along the coastal ledges.

Building sites

Areas constructed for car traffic, preferably avoiding direct connections with the protected areas. They have the potential to offer a variety of outdoor recreational activities, though with this comes damage to the land. Given that man-made structures are in this type of area, they are also near to car parks and the hubs of outdoor activity in Öskjuhlíð. These areas include the surroundings of Perlan, Sólland and Leynimýri, the Nauthólsvík area, and the area surrounding the bowling alley.

Constructions and protection areas

Areas where importance of nature and historical relics must be taken into account when new developments are being constructed. These include the quarry next to the bowling alley, and the Nauthólsvík area.

According to Yngvi Loftsson, the terrain analysis was taken into account in Reykjavík’s new municipal plan for 2010-2030, as well as other plans such as the conservation of ancient shore boundaries and artifacts on the western slopes, and the protection of the Fossvogur banks.

“It has also proven to be very useful in the discussion and promotion of the area, as the presentation of the analysis highlights its distinctive characteristics as well as laying the foundations for the land-use planning proposal. In accordance with the proposal, plans were made for a bus route or light rail tracks along the south and west slopes, but these plans have since been scrapped in favor of a bike track and a planned tunnel under Öskjuhlíð.“

Ready, set, competition

In the fall of 2013 the City of Reykjavík held a competition on proposals for the utilization of the Öskjuhlíð area. The terms of the competition were based upon the analytical methods used in the land-use planning. The ideas were supposed to center around preservation and development with the goal of improving the area. The landscape architects Landslag won the competition. Established in the 1960s, the agency has been one of Iceland’s leading agency in it’s field ever since.

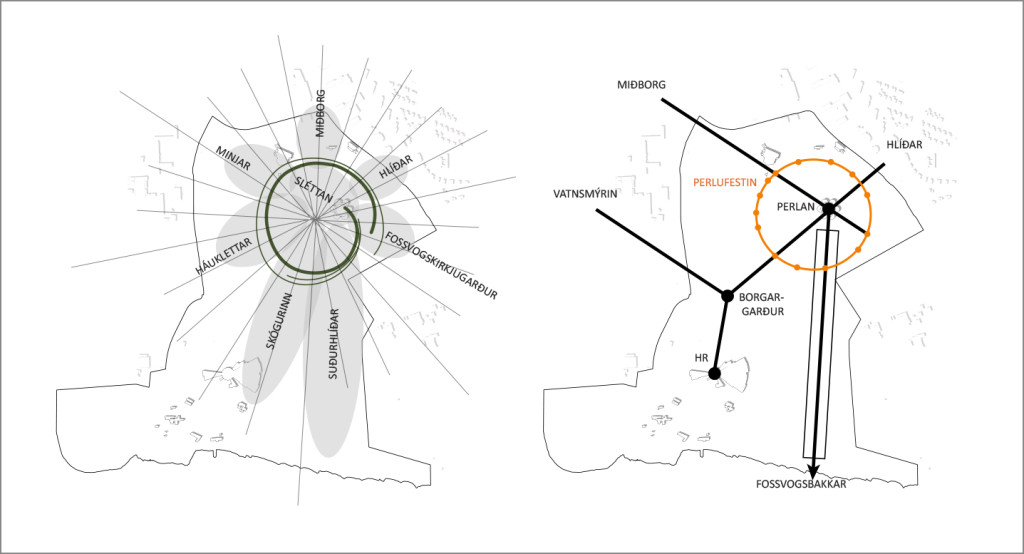

“The concept behind the winning proposal is based around the concept of beams of light radiating out across the area from the center of Perlan. The proposal also takes inspiration from the idea of a string of pearls, interpreted as a path forming an easily-walked, almost horizontal circuit which threads together the many interesting sites that Öskjuhlíð has to offer.“ says Þráinn Hauksson of Landslag.

The rays are intended to define the connection between the area and its environment, and to facilitate overview of the area, figuratively lighting the way around Öskjuhlíð. Particular areas of focus are on the pathways where the beams intersect the strings of pearls on one side, and the main walkway to the west of Öskjuhlíð the other side.

Left: Beams from the top connect the surrounding areas. Right: A circle around Perlan connects interesting places. Images from Landslag architects.

Þráinn says that his team aims at ensuring that Öskjuhlíð will continue to be defined by the natural treasures hidden within. The historical relics are to be protected and given higher priority with labels and information signs. The well organized path system will enable a greater variety of possibilities in the area. Emphasis is placed on keeping the open meadow to the west of Perlan as it is. The proposition also allows the tank landfills can be further developed as a climbing and high adrenaline sports area, and the forest will become a setting for mountain biking on designated tracks.

When asked about the city’s implementation of the winning proposal Þráinn admits he does not have a good answer. “The competition was a search for ideas and nothing has been promised. Nonetheless I’m sure our proposal could open up a lot of opportunities for the area and attract more people to this jewel in the middle of Reykjavík.“